The role nutrition plays in the development, maintenance and management of chronic pain. Part 2: What?

Part 2 – What is nutrition and why is it important?

Diet versus nutrition

“Diet is the sequence and balance of meals in a day”, in other words, what you eat and how often. Whereas, nutrition is the interaction between our body and that food.

Nutrition is made up of nutrients, macronutrients (carbohydrates, protein and fat) and micronutrients (vitamins and minerals). Each of these components make up a well-balanced diet and good nutrition:

- Macronutrient: these are large nutrients, which we require large amounts of. They provide the “building blocks” for the body and calories we need for energy.

- Micronutrient: these are small nutrients, which we only require small amounts of. They are found in abundance in plant-based foods and are “protective” reducing inflammation and oxidative stress.

Good nutrition is essential for your health and well-being. What we eat and drink becomes the foundation for our overall health and well-being: making up the structure, function and integrity of every single cell in our bodies. An overview of good nutrition includes:

- Carbohydrates consist of monosaccharides and disaccharides – simple carbohydrates – and polysaccharides – complex carbohydrates – these can be utilised to keep us alive and warm, build and repair tissue, and move.

- Protein can be derived from plants or animals and play an important role in hormones, tissue repair, preserving lean muscle mass, and supply energy when carbohydrates aren’t available.

- Fats consist of saturated – “unhealthy fats” – and unsaturated dates – “healthy fats” – these are concentrated energy supplies which can be stored for later, and utilised for building cells.

- Water is essential for life, it makes our bodily fluids, builds our cells, removes toxins for our body and cushions our brain and spinal cord.

- Fibre consists of soluble – dissolves in water and encourage the growth of our gut bacteria in the large intestine – and insoluble – which moves through the large intestine intact, and helps to bulk our stools and prevent constipation – which maintain gut health and digestion.

- Minerals play a vital role in the health of soft tissue, bodily fluids and our bones.

- Vitamins play a vital role in normal bodily functions, preserving health and wellbeing. They are divided into fat soluble (vitamins A, D, E and K) – requires fat to utilise these vitamins and can be stored – and water soluble (vitamins B, C and folic acid) – requires water to be utilised and cannot be stored.

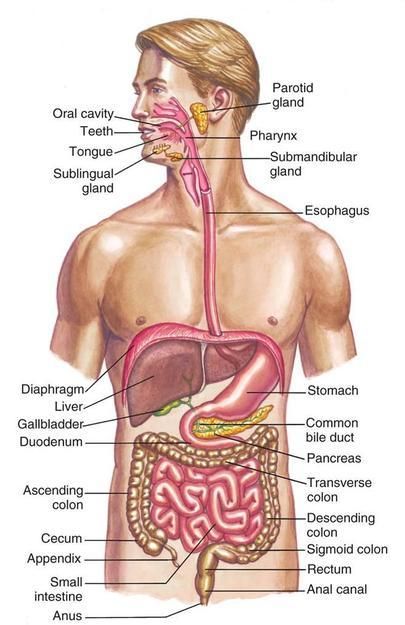

The digestive system

Our digestive system, is made up of a group of organs including our mouth, salivary glands, oesophagus, stomach, panaceas, liver, gallbladder, appendix, small intestine, large intestine, rectum and anus.

Our digestive system, is made up of a group of organs including our mouth, salivary glands, oesophagus, stomach, panaceas, liver, gallbladder, appendix, small intestine, large intestine, rectum and anus.

The process of digestion breaks down the food we eat into the nutrients and energy we need to live and thrive.

At each level of our digestive system – from when it enters and then exits our body – food is being broken down and converted, so that we can repair, grow and survive. This process can take up to 40-50 hours.

Our digestive system also works as a guard and barrier, keeping the contents within, from escaping into the bloodstream until they are ready and safe to do so.

It also performs many other vital functions including:

- Sustaining and protecting our overall health and well-being

- Allowing us to absorb water and nutrients from the food we eat

- Converting food into the building blocks our bodies need to live, function and stay healthy

- Producing and/or hosting many of our neurotransmitters – including serotonin and GABBA, which mediate descending analgesic pathways

- Supporting our immune system

- Communicating with our brain (the gut-brain axis)

- Playing host to more than 100 million nerve cells (The Enteric Nervous System)

- Modulating stress, mood, pain and our general state of mind

- Feeding and hosting our gut microbiome (the 100 trillion microorganisms and their genetic material which live within our gut and help our digestive process)

Understanding calories and the role they play in weight

According to an article published by the Open University, “when you turn on the engine of a car, the petrol combines with oxygen and ‘burns’ to make energy. The energy makes the car move, and it also makes the engine warm. Similarly, the body ‘burns’ nutrients to make energy.”

85% of our daily energy comes from fat and carbohydrates and 15% from protein; energy is measured in calories or kilo-joules. When our body is in balance (there are no other underlying health issues, hormone imbalances, and you are not in a period of prolonged stress):

- To maintain a healthy weight your “energy in” needs to be equal to your “energy out”

- To gain weight your “energy in” needs to exceed your “energy out”

- To lose weight your “energy out” needs to exceed your “energy in”

The calories we burn every day, also known as our total daily energy expenditure (TDEE), is made up of the following factors:

- Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR): energy used to stay alive (active when digestive system inactive)

- Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR): energy used to sustain body whilst resting and perform basic bodily functions

- Thermogenic effects of food (TEF): energy used to break down food, utilise the nutrients and remove waste products

- Exercise: the energy used to perform aerobic activity

- Excess post-exercise oxygen consumption (EPOC): the energy used after a workout. High intensity interval training and TABATA are known for increasing this.

- Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT): energy used for normal day-to-day activities, not sleeping or eating.

Whilst our resting metabolic rate and the thermogenic effects of food remain fairly constant, our lifestyle has a significant impact on the other factors listed above and our weight. Some interesting facts about calories include:

- We can burn anywhere from 1000 -2000 calories just staying alive each day (link)

- We burn about 320 calories thinking every day, this increases by 5% depending on the complexity of the thought (link)

- We burn anywhere from 50-500 calories during the night whilst we are asleep (link)

Weight loss or gain is considered 80% diet and 20% exercise. When our body is in balance (as discussed above), most areas of weight management fall under 3 types of restriction to diet:

- Caloric restriction: how much we eat, the quantity consumed

- Time restriction: when we do and don’t eat (intermittent, time-restricted fasting etc.)

- Dietary restriction: what we eat and what you don’t (paleo, vegetarian, vegan, plant-based, carnivore etc.)

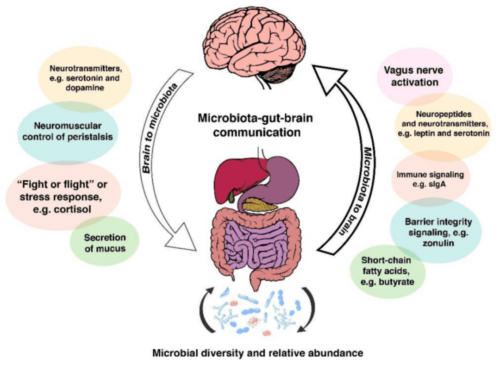

The role of the gut-brain axis

Much like a car and the fuel it receives, our brain functions at its best when we give it a well-balanced diet. When it is deprived of good-quality nutrition it can affect our mental health and mood, sleep, physical health, immune system, and pain. This is partly due to the bidirectional relationship between our brain and digestive system: known as the gut-brain axis.

Much like a car and the fuel it receives, our brain functions at its best when we give it a well-balanced diet. When it is deprived of good-quality nutrition it can affect our mental health and mood, sleep, physical health, immune system, and pain. This is partly due to the bidirectional relationship between our brain and digestive system: known as the gut-brain axis.

Our central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) communicates with the enteric nervous system (nervous system found in the gut) through a complex communication network known as the gut-brain axis.

The enteric nervous system (ENS) is a part of our autonomic nervous system (subconsciously controls and regulates our internal organs); an intricate network of 50-100 million nerve cells which reside and communicate within it. This complex network of nerve cells allows us to monitor, communicate and integrate information from our gut to the rest of our bodies. It also controls movement throughout the gut (peristalsis), exchange of fluids to assist with digestion (digestive juices) and maintains blood flow.

The gut-brain axis also involves the:

- Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis – primarily involved in the short-term adaptive (reactive, purposeful, proactive) response to stress and the long-term maladaptive (dysfunctional, nonadaptive) response to chronic stress, which results in a positive feedback loop (generates a vicious cycle)

- Gut microbiome – the 100 trillion microorganisms and their genetic material which live within our digestive tract, which break down nutrients, allowing them to be absorbed and producing short-chain fatty acids which the brain uses

- Gut permeability – the gut wall is a communication channel between our body and the microbiota: acting as a barrier permitting certain molecules to pass, whilst preventing others. The purpose of this is to support immune and brain function.

- Neurotransmitter production – 90% of serotonin is produced in the gut. It is responsible for improved mood and sleep, as well as modulating pain perception.

- Immune function and inflammation

Gut microbiome

For over 15 million years, humans have co-evolved with the gut bacteria which lies within their large intestine. This gut bacteria: digests the parts of our diet which we are unable to break down on our own (predominantly fibre); it assists us to create vitamins, neurotransmitters and hormones; it trains our immune system and guards it against unwanted pathogens; and it assists with the growth of cells within our gut.

But with the multitude of changes to our diet and lifestyle over the last 200 years, we have seen an influx of changes to our health, gut bacteria and the chronicity of diseases. Studies looking at the Hazda people who still live as hunter-gathers, have shown how a seasonal diet of meat, berries, tubers, baobab (a fruit) and honey, changes their gut bacteria within hours of the meal they digest. The Hazda people have showed a constantly changing and evolving bacterial landscape, which moves with their diet. They also showed higher levels of bacterial richness and diversity, which scientists believe would have been similar to the people living 15 million years ago. But why does our diet have such a dramatic influence on our gut bacteria and why is it so hard to change our diets?

The answer could lie in the fact: our gut bacteria share the food we eat, and they each have their own appetites: yeast eat sugar, Bacteroidetes crave fat, Prevotella enjoy carbs and Bifidobacteria love fibre. When they are unable to have their appetite met, they can either produce toxins which make us feel less than our best, resulting in headaches, stomach aches or irritability, or increase our cravings for their food source. This means your diet can either make your gut bacteria flourish and multiply when you feed it the right food, or starve and die. It also explains why it can take a while to change your diet and the cravings associated with those changes.

When it comes to diet and our gut bacteria, there is not a one-size-fits-all approach. A study completed in 2019 by two researches in Israel highlighted how differently 2 people can respond to the same meal, and how this potentially comes down to how quickly their gut bacteria breaks down the food they eat and allows them to absorb it. This highlights how unique our gut bacteria are, much like a fingerprint, and how a personalised diet may assist us on our journey to better gut health.

Interestingly, researchers are only just learning how our gut microbiome may also plays a role in the development, maintenance and management of chronic pain.

What makes up a well-balanced diet

Carbohydrates:

As we discussed above, our body needs energy to keep us alive and get through the day. This energy is predominantly derived from carbohydrates. Carbohydrates are present in fruit, vegetables, seeds and grains, but also many processed foods including sugary foods.

They are digested in your small intestine, broken down and absorbed into the bloodstream for energy. Some sugars are converted into glycogen and stored in the liver (being released as a blood glucose for energy) or muscle (for muscle activity). If glycogen is not used, it is converted into fat.

Nutritious types of carbohydrates include:

- Dietary Fibre found in plant-based foods (legumes, fruits, nuts, seeds, vegetables and wholegrains).

- Complex carbohydrates found in starches (legumes, nuts, potatoes, rice, wheat, grains, quinoa, burgul, couscous, polenta, flour, pasta, cereals).

- Sugars, including glucose (fruit, honey and some vegetables), fructose (fruit and honey), maltose (malted grains), sucrose (sugar cane) and lactose (milk, including breast milk)

Glycemic index (GI) relates to the speed carbohydrates are digested into glucose and energy.

- Low Gl foods are broken down slowly and help you feel full for longer

- High GI foods are broken down quickly, causing a spike in blood glucose levels

GI levels do not necessarily correlate with health and nutrition. It is important to look at the nutritional value of a food as a whole to determine its health benefit.

According to the Nutrition Australia:

- Women should be eating:

- 5 servings of vegetables and legumes per day

- 2 servings of fruit per day

- 4-6 servings of grains per day

- Men should be eating:

- 5-6 servings of vegetables and legumes per day

- 2 servings of fruit per day

- 6 servings of grains per day

Carbohydrates and chronic pain

According to research, we should be eating 3 portions of healthy lower glycemic index carbohydrates each day, to reduce inflammation and oxidative stress, commonly associated with chronic pain (learn more about this research here). Research also suggests, a diet high in fruits, vegetables and polyphenols, reduces inflammation and protects against oxidative stress (learn more about this research here).

Learn more

-

- To learn more about carbohydrates visit Health Direct or Eat for Health.

- To learn more about glycemic index visit Dietitian’s Australia.

Protein

Protein is used by our body to grow and repair, it also acts as a source of energy when the is insufficient carbohydrates available. Protein is broken down in the stomach and duodenum into polypeptides, then exopeptidases and dipeptidases and then into amino acids.

There are 20 different amino acids which are utilised by our body to fight infections, create enzymes and hormones, provide structure and support to cells, and transport atoms and molecules. Nutritious sources of protein include lean meat, poultry, fish, eggs, milk, nuts, seeds, legumes and beans.

According to Nutrition Australia:

- Women should be eating 2-2.5 servings of lean meat, fish, poultry, eggs, nuts, seeds, legumes and beans per day

- Men should be eating 5-3 servings of lean meat, fish, poultry, eggs, nuts, seeds, legumes and beans per day

Protein and chronic pain

According to research, we should be eating 4 portions of fish daily, or 2 portions of eggs daily, or 2 portions of white meat daily and 1 portion of red meat weekly to reduce inflammation and oxidative stress (learn more about this research here).

Learn more

- To learn more about protein visit Health Direct or Eat for Health

Dietary Fat

Fat have had some bad press over the past couple of decades, but they are actually an essential part of our diet; being utilised as: energy, supporting cell growth, keeping us warm and protecting our organs. Fat is responsible for the following functions:

- Protecting vital organs

- Storing energy for times when food is less abundant

- Regulating glucose and cholesterol

- Metabolism of sex hormones, including atomatase (link)

- Releasing adiponectin – which improves sensitivity to insulin and protects against type 2 diabetes (link)

- Releasing cytokines (TNF alpha, IL-6 and leptin) – which allow cells to communicate with one another (link)

- Releasing plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 – responsible for blood clotting (link)

- Releasing angiotensin – involved in maintaining blood pressure (link)

- Releasing lipoprotein lipase and apolipoprotein E – which assist with the storage and metabolism of fat for energy (link)

Types of fat include:

- Saturated – these fats tend to be solid when at room temperature and increase cholesterol levels and risk of stroke and heart disease. Sources of saturated fats include meat, cream, butter, cheese, dairy products, coconut oil, palm oil and takeaway.

- Trans fats – there are 2 different types of trans fats, naturally occurring which are produced in the gut and artificially occurring – which are made through processing oils to make them more solid (by adding hydrogen). Trans fats raise your bad (LDL) cholesterol and lower your good (HDL) cholesterol levels, increasing the risk of stroke, heart disease and type 2 diabetes. Sources of trans fats include processed and packages foods.

- Monosaturated fats – these are beneficial for your health (reducing blood cholesterol levels, risk of heart disease and stroke) and tend to be liquid when at room temperature. Sources of monosaturated fats include olive oil, canola oil, peanut oil, safflower oil, sesame oil, avocados, peanut butter, and many other nuts and seeds.

- Polyunsaturated fats – these are also beneficial for your health and tend to be liquid at room temperature. Sources of polyunsaturated fats include soybean oil, corn oil, sunflower oil, tofu, walnuts and flaxseed.

Omega-3, -6 and -9 are all important dietary fats which contribute to our overall health, but is it very important to get the right balance of each because an imbalance can actually contribute to chronic disease.

Omega-3 essential fatty acids: Omega-3 is an essential fatty acid which your body is unable to produce. According to the National Institute for Health, we should eat 2 portions of oily fish high in omega-3 every week. Food high in omega-3 include salmon, mackerel, sardines, anchovies, chia seeds, walnuts and flaxseeds.

Omega-3 improve heart health; support mental health, including symptoms of depression, bipolar and schizophrenia; reduce weight and waist size; decrease liver fat; support infant brain development; prevent dementia; promote bone health; prevent asthma; and according to emerging evidence may reduce the need for anti-inflammatory medication and reduce the risk or effects of inflammatory diseases such as chronic pain and rheumatoid arthritis.

Omega-6 essential fatty acids: Omega-6 is also an essential fatty acid which is used primarily for energy, but high amounts can lead to inflammation in the body, typically you should have 4 servings of omega-6 for every 1 serving of omega-3. Foods high in omega-6 include soybean oil, corn oil, mayonnaise, walnuts, sunflower seeds, almonds and cashew nuts.

Omega-9 fatty acids: Omega-9 can be produced in the body and are found in almost every cell in our body, they are responsible for assisting us with our “bad fat” levels, inflammation and cholesterol levels. Foods high in omega-9 include olive oil, cashew nut oil, almond oil, avocado oil, peanut oil, almonds, cashews and walnuts.

According to the Australian Healthy Food Guidelines:

- Women should have an average of 14-20 grams of healthy fat per day

- Men should have an average of 28-40 grams of healthy fat per day

Fats and chronic pain

According to research, we should be having 2-3 portions of olive oil and/or omega-3, to reduce inflammation and increase antimicrobial and antioxidant activity (learn more about this research here). Research also suggests, increasing good quality fats through a diet high in omega-3 and olive oil: reduces inflammation and improves immunity (learn more about this research here)

Learn more

- To learn more about fats visit Eat for Health or Health Direct.

- To learn more about Omega-3, -6 and -9 visit Healthline.

Water

Water is a vital part of our diet. Our body is made up of 50-75% water, which is found in every cell of our body, including our bones, fat and lean muscle. Water forms our blood, digestive juices, urine, cerebrospinal fluid and perspiration. The amount of water required each day varies depending on our age, body size, metabolism, diet, activity levels and the weather.

According to the Australian Healthy Food Guidelines:

- Women should drink an average of 2 litres of water per day

- Men should drink an average of 2.6 litres of water per day

Water and chronic pain

According to research, we should be drinking 1.5-2 litres of water per day to avoid dehydration (learn more about this research here). Increasing water intake reduces increased sensitivity to pain associated with dehydration (learn more about this research here).

- To learn more about the role of water in our diet visit the Better Health Channel

Fibre

Fibre is an essential part of diet which is derived from parts of plants which cannot be absorbed or digested by our body. Fibre assists with our digestion and moving of waste products through our digestive tract. Fibre moves through our digestive tract to the large intestine where it is broken down by our gut bacteria.

There are different types of fibre which works in different ways within out gut:

- Soluble fibre: which can be dissolved in water and encourage the growth of our gut bacteria in the large intestine. This type of fibre has been shown to assist with reducing blood cholesterol levels, lowering fat absorption, helping weight management, stabilising our blood sugar levels and reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease. Some good sources of soluble fibre include: citrus fruits, oats, beans, peas, oats, barley and apples.

- Insoluble fibre: This type of fibre moves through the large intestine intact, and helps to bulk our stools and prevent constipation. This type of fibre has been shown to help prevent gastrointestinal blockages and lower the risk of diverticular diseases and some cancers. Some good sources of insoluble fibre include: bran, whole wheat, green beans, cauliflower, nuts, potatoes and beans.

- Resistant starch: Although not a fibre per se, it acts much like insoluble fibre in our gut, moving through to our large intestine where it helps to build our gut bacteria. Some good sources of resistant starch include: ‘al centre’ pasta, raw oats, under-ripe bananas and cooked then cooled potatoes.

Fibre is vital for gut health because of the role it plays in preventing many gut-related issues including constipation, irritable bowel syndrome, diverticular disease, haemorrhoids and bowel cancer. Fibre also acts as a source of food to our gut bacteria, and transportation to assist with the removal of waste products from our digestive tract. Fibre also acts to prevent opioid-related constipation.

According to the Nutrition Australia:

- Women should be eating 25g of fibre a day

- Men should be eating 30g of fibre a day

Fibre and chronic pain

According to research, improving digestion and having a healthy gut microbiome, reduces the risk of opioid related constipation and potentially plays a role pain management (learn more about research this here).

Learn more

- To learn more about fibre download this fact sheet.

- To learn more about meals you can cook to increase your fibre intake download this fact sheet.

Food to avoid

With the rise of many lifestyle and diet-related diseases, the role nutrition plays in health has never been so widely recognised. The WHO acknowledges

“nutrition is coming to the fore as a major modifiable determinant of chronic disease, with scientific evidence increasingly supporting the view that alterations in diets have strong effects (both positive and negative) on health throughout life”.

According to this article produced for The Lancet, the leading dietary risk factors include high sodium intake, low whole grain intact and low fruit intake. According to its findings 50% of deaths and 66% of DALYs (disability-adjusted life years) are attributed to diet, and an improvement in diet could prevent one in five deaths globally.

So, what should we avoid?

Saturated fats – linked to increased risk of heart disease and high blood cholesterol levels. These are usually solid when at room temperature and found in palm oil, coconut milk and cream, cooking margarine, fatty-cuts of meat, processed meats, takeaway and many packaged snack foods.

Refined sugar – linked to many chronic diseases due to the role it plays in oxidation and inflammation, and type 2 diabetes. These are primarily derived from plants such as sugar cane and added to cakes, biscuits, soft drinks, packaged foods and takeaway.

Salt – linked to increased risk of high blood pressure, heart disease, stroke and chronic kidney disease. Found in packaged or bottled foods, pre-made sauces and spice mixes, and takeaway.

For a full break down of these foods and the serving sizes, visit Eat for Health.

Lifestyle factors

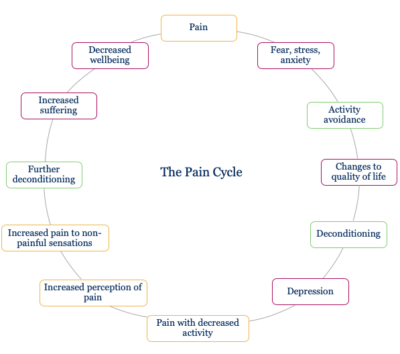

The gut-brain axis and the role our gut microbiome plays in our health may explain why there is such a strong link between so many areas of nutrition and the pain cycle. It may also explain why nutrition-related behaviours or complementary lifestyle activities we take on, can either improve or remove from our health, well-being and pain.

Beneath is an overview of some of these lifestyle factors:

Physical Activity

Physical activity plays a role in weight management; emotional and mental health; physical health including sleep, pain and disability. The old sayings “if you don’t move it, you lose it” and “motion is lotion” are both true when it comes to chronic pain.

Physical activity “when applied within appropriate parameters (frequency, duration and intensity)” significantly improves pain and the pain cycle. Physical activity also reduces metainflammation, which is linked to central sensitisation, in the context of weight loss and obesity (link).

Sleep

Sleep also plays an important role in weight management; emotional and mental health; physical health including sleep, pain and disability. Sleep has been shown to strongly correlate with hormonal and metabolic processes; hormones which impact on appetite and hunger; meal choice and eating behaviours; the function of the glymphatic nervous (responsible for removing waste products from our CNS); and gut microbiome. Sleep plays a role in reducing inflammation and insulin resistance, as well as pain sensitivity, the duration of painful episodes and pain intensity.

Stress

Stress also play another important role. Stress has been shown to directly impact on obesity, meal choices, quantity of food eaten, and the distribution of adipose “fat” tissue.

Stress and chronic pain are both affected by the limbic brain – hippocampus, amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex – with a structural and physiological remodeling in its pathways and communication channels. Stress and pain are adaptive protective responses which can become maladaptive over the long-termcausing a negative impact on health and well-being; the challenge is they also feed into one another, each exacerbating the other.

The chronicity of stress and pain can both contribute to high levels of cortisol and adrenaline, which can affect metabolism and weight. The reason for this affect, includes:

- Increasing the secretion of glucose from your liver, which increase your blood sugar levels

- Decreasing the hormones responsible for removing excess glucose from your blood – insulin

- Glucose being stored as fat

- Decreasing the ability to clear excess hormones from your liver, leading to increasing circulation of unnecessary hormones like cortisol, oestrogen etc.

- Increasing our appetite and attention to food (this is due to our cave men “fight or flight” memory that prolonged stress usually meant famine or food shortage)

- Storing excess weight to weather the storms (once again due to the “fight or flight” memory).

Prolonged stress can prevent effective weight-loss by traditional means, such as calorie restriction because this only further reinforces the message that there is a food shortage, and exercise only adds further fuel to our “fight or flight” stress response – as exercise activates this sympathetic nervous system response in our bodies.

Some additional side effects of prolonged stress include imbalances to our sex-hormones, such as oestrogen dominance; changes to our hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis; and changes to our thyroid and growth hormones; all of which have an impact on healthy weight, metabolism and weight-loss.

Often in situations of prolonged stress and chronic pain, the initial, most effective weight management strategies come from stress-management, deep breathing exercises (our breath is the only way to tap into our sympathetic nervous system), relaxation activities (such as meditation, yoga and Tai Chi), lower intensity exercises (such as hydrotherapy, walking, resistance training and stretching) and small, regular, healthy meals. These activities reduce the positive feedback loop – “fight or flight” – created in our body.

Sunshine

Time outside in the sun also play another important role. Vitamin D is essential for energy levels, digestion, immunity, inflammation, skin problems, blood pressure, mood stability and weight management.

Our skin produces large volumes of Vitamin D when exposed to sunlight. Vitamin D helps build strong bones; regulate the immune system and our neuromuscular system; and plays a major role in the life cycle of cells. This is because every tissue in our body has vitamin D receptors (bones, muscles, immune cells and brain cells). Research also highlights how low levels of vitamin D has a strong relationship to the development and maintenance of chronic pain.

Social Interaction and meaningful activity

Social interaction and meaningful activity play another important role. Research suggests that social isolation increases the risk of mortality and morbidity, it also is strongly linked to increased weight gain, adipose “fat” tissue, poor diet.

Social isolation is also a high-risk factor for people living with chronic pain and strongly impacts on physical function and pain interference. Research suggests that improving social interaction and engaging in meaningful activity improves function and quality of life, and has a flow on effect on positive lifestyle behaviours, such as diet, physical activity and reduced stress levels.

All of these lifestyle factors also play a contributing role in the suffering experienced by those living with chronic pain. They can create a positive-feedback loop which exacerbates pain, decreases function and increases disability and other co-morbidities.

A little bit about feedback loops

As we discussed above, stress and chronic pain can create positive feedback loops. Feedback loops are how the human body generates a cascade of bodily processes to either protect or prevent problems. Negative feedback loops involve a response which tries to reverse the change detected and promote balance in the body, whereas positive feedback loops try to promote or reinforce the effect detected and maintain it.

There are numerous times when our body can get this wrong, particularly in chronic illness, where it creates loops of inflammation and/or oxidation, and unhelpful behaviours, thoughts and emotions.

Acute pain: our body generates a set of functions that create a positive feedback loop aimed at protecting us, and avoiding the risk of harm or damage. The pain itself, prevents us using the injured area, concentrating our emotions and behaviours around protection and alleviation. This allows our body to heal and repair, and once this is done, the pain eases and then eventually stops. This positive feedback loop is often maintained in chronic pain, creating maladaptive “unhelpful” responses, for example excessive rest or using unhelpful short-term fixes to cope with the ongoing pain.

How nutrition can play a role in chronic pain

The pain cycle is a concept used to explain the flow-on effects of pain on every aspect of a person’s life. It looks at how pain changes our ability to exercise, our mood, our sleep and our diet. The longer pain continues the greater the cascade of issues, creating a positive feedback loop, which exacerbates this cycle.

The pain cycle is a concept used to explain the flow-on effects of pain on every aspect of a person’s life. It looks at how pain changes our ability to exercise, our mood, our sleep and our diet. The longer pain continues the greater the cascade of issues, creating a positive feedback loop, which exacerbates this cycle.

The pain cycle is responsible for:

- Physical, mental and emotional changes

- Changes to energy levels

- Changes to appetite

- Disturbances in sleep disturbances

- Metabolic changes, to name a few.

Each of these factors can be positively or negatively impacted by nutrition and lifestyle. Often looking at the enormity of this cycle is too much to take on, so active self-management strategies in pain management aim to look at each issue independently, working on simple strategies to tackle these and improve function and quality of life. One such active self-management strategy is modifying diet.

As we highlighted in part 1, nutrition directly relates to chronic pain due to the impact it has on the nervous, immune and endocrine systems; on joint-load and metainflammation; and the risk/severity of other chronic diseases. Nutrition plays a role in the development, maintenance and management of chronic pain.

The severity, maintenance and interference experienced with chronic pain is also strongly influenced by physical activity levels, stress levels, sleep disturbances and mood. Interestingly, each of these factors is also influenced by nutrition, which is why targeting diet may improve each of these factors.

Conclusion

The food we eat becomes the foundation of every cell within our body. What we eat contributes to our health and well-being, allowing us to live, breath and get through the day. Our diet is also strongly linked to our sleep, mood, stress levels, pain levels and many of the chronic illness that are now prevalent around the world. In part 3 we will discuss how to improve your diet and nutrition based on the latest research. Continue reading part 3 here.

Learn more

Nutrition and Diet Resources

- 2020 European Year for the Prevention of Pain Factsheet: Nutrition and Chronic Pain Factsheet

- Webinar: IASP Webinar: Why, what and how of nutrition for people experiencing chronic pain (link)

- Website: University of Newcastle: Free Healthy Eating Quiz, Report and Recommendations (link)

- Article: NPC: 12 Quick Tips for Improving Your Nutrition (link)

- Article: NPC: Guide to Healthy Diet and Weight Management (link)

- Article: PPM: A Diet for Patients with Chronic Pain (link)

- Article: NHS: Improving health and fitness (link)

- Factsheet: HNEHealth: Nutrition and pain (link)

- Factsheet: ACI: Pain: Lifestyle and nutrition (link)

- Website: Eat for Health (link)

- Website: The Australian Dietary Guidelines (link)

- Website: The Australian Healthy Food Guide (link)

- Article: Health Engine: Pain and Nutrition (link)

- Article: Dietician’s Australia: Smart eating for you (link)

- Article: My Joint Pain: Healthy Eating and Arthritis (link)

- Article: My Joint Pain: Nutrition (link)

- Article: Find an Accredited Practising Dietitian (link)

- Article: Back to Basics: Recipes (link)

- Article: AIHW: Food and Nutrition (link)

- Article: NHMRC: Nutrition (link)

- Article: Healthdirect: A balanced Diet (link)

- Article: IPSI: Diet & Pain: Part 1: Which diet works best for pain (link)

- Article: IPSI: Diet & Pain: Part 2: Which diet works best for pain (link)

- Article: Future Medicine: Diet therapy in the management of chronic pain: better diet less pain? (link)

Gut Health Resources

- Article: NPC: 12 Quick Tips for Improving Gut Health (link)

- Article: NPC: Gut Health and Pain – Part 1: Know Your Gut (link)

- Article: NPC: Gut Health and Pain – Part 2: The Gut-Brain Connection (link)

- Article: NPC: Gut Health and Pain – Part 3: Your Gut and Stress (link)

- Article: NPC: Gut Health and Pain – Part 4: Changing your Gut Health (link)

- Article: Harvard Health: Can diet heal chronic pain? (link)

- Article: Science Daily: Gut bacteria associated with chronic pain for first time (link)

- Article: PPM: Gut Health: A look inside reveals what you eat can affect your pain (link)

- Article: IPSI: Chronic Pain Treatment by Healing the Gut (link)

- Article: PBHC: The Gut-Brain Connection to Chronic Pain, Anxiety and Depression (link)

Smoking Resources

- Factsheet: Australian Government: How to quit smoking (link)

- Factsheet: NSW Health: Smoking, your health and quitting (link)

- Article: NPC: Benefits of Quitting Smoking (link)

- Article: Pain Science: Smoking and Chronic Pain (link)

- Article: Cancer Council: Quit Smoking (link)

- Article: The Lung Foundation: Quitting Smoking (link)

Alcohol Resources

- Factsheet: ACI: Standard Drinks (link)

- Website: Drinkwise (link)

- Website: Alcoholics Anonymous (link)

- Article: NIAAA: The Complex Relationship Between Alcohol and Pain (link)

Recreational Drugs Resources

- Article: NSW State Library: Drug Information (link)

- Website: Reach Out: Addiction (link)

- Website: Alcohol and Drug Foundation (link)

Free Worksheets

- Booklet: Guide to Nutrition for Chronic Pain (link)

- Worksheet: Weekly Food Diary (link)

- Worksheet: My Health Plan (link)

- Worksheet: Weekly Food Diary (link)

Other References

- Journal Article: Dietary Polyphenols—Important Non-Nutrients in the Prevention of Chronic Noncommunicable Diseases. A Systematic Review (article here)

- Journal Article: Curcumin Could Prevent the Development of Chronic Neuropathic Pain in Rats with Peripheral Nerve Injury (article here)

- Journal Article: Omega-3 Fatty Acids (Fish Oil) as an Anti-Inflammatory: An Alternative to Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs for Discogenic Pain (article here)

- Journal Article: Effects of soy diet on inflammation-induced primary and secondary hyperalgesia in rat (article here)

- Journal Article: Diet-induced obesity: dopamine transporter function, impulsivity and motivation (article here)

- Journal Article: Neuroinflammation and central sensitisation in chronic and widespread pain (article here)

- Journal Article: Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health (article here)

- Journal Article: Nutritional intervention in chronic pain: an innovative way of targeting central nervous system sensitization? (article here)

- Article: ICP: What is central sensitisation (link here)

- Journal Article: Neuroinflammation: The devil is in the details (article here)

- Journal Article: Eubiosis and dysbiosis: the two sides of the microbiota (article here)

- Article: Our gut microbiome is always changing; it’s also remarkably stable (link here)

- Book: Gut Health and Probiotics. The science behind the hype. Jenny Tschiesche

- Book: Rushing Woman’s Syndrome. The impact of a never ending to-do list on your health. Dr Libby Weaver

- Book: Gut. The inside story of our body’s most under-rated organ. Giulia Enders

- Book: The mind-gut connection. How the hidden conversation within our bodies impacts on our mood, our choices, and our overall health. Emeran Mayer, MD

- Journal Article: The role of gut microbiota in immune homeostasis and autoimmunity (article here)

- Journal Article: The Role of Gut Microbiota in Intestinal Inflammation with Respect to Diet and Extrinsic Stressors (article here)

- Journal Article: Gut microbiota functions: metabolism of nutrients and other food components (article here)

- Journal Article: Stress and the gut microbiota-brain axis (article here)

- Journal Article: The gut microbiome: Relationships with disease and opportunities for therapy (article here)

- Journal Article: Neurotransmitter modulation by the gut microbiota (article here)

- Journal Article: Human nutrition, the gut microbiome and the immune system (article here)

- Journal Article: The microbiome: A key regulator of stress and neuroinflammation (article here)

- Journal Article: Current Understanding of Gut Microbiota in Mood Disorders: An Update of Human Studies (article here)

- Journal Article: Role of gut microbiota in brain function and stress-related pathology (article here)

- Journal Article: Intestinal permeability – a new target for disease prevention and therapy (article here)

- AUSMED E-Learning: Gut Microbiota Health and Wellbeing (link here)

- Journal Article: A review of lifestyle factors that contribute to important pathways associated with major depression: Diet, sleep and exercise (article here)

- Journal Article: ‘Gut health’: a new objective in medicine? (article here)

- Journal Article: Impact of the gut microbiota on inflammation, obesity, and metabolic disease (article here)

- Journal Article: Is eating behavior manipulated by the gastrointestinal microbiota? Evolutionary pressures and potential mechanisms (link here)

- Journal Article: Effects of Diet on Gut Microbiota Profile and the Implications for Health and Disease (link here)

- Journal Article: The gut microbiome: Relationships with disease and opportunities for therapy (link here)

- Article: Hunter-gatherers’ seasonal gut-microbe diversity loss echoes our permanent one (link here)

- Journal Article: Fiber-Mediated Nourishment of Gut Microbiota Protects against Diet-Induced Obesity by Restoring IL-22-Mediated Colonic Health (link here)

- Journal Article: The hot air and cold facts of dietary fibre (link here)

- Journal Article: Commensal bacteria and essential amino acids control food choice behavior and reproduction (link here)

- Journal Article: Eubiosis and dysbiosis: the two sides of the microbiota (article here)

- Article: Our gut microbiome is always changing; it’s also remarkably stable (link here)

- Journal Article: The role of gut microbiota in immune homeostasis and autoimmunity (article here)

- Journal Article: The Role of Gut Microbiota in Intestinal Inflammation with Respect to Diet and Extrinsic Stressors (article here)

- Journal Article: Gut microbiota functions: metabolism of nutrients and other food components (article here)

- Journal Article: Stress and the gut microbiota-brain axis (article here)

- Journal Article: The gut microbiome: Relationships with disease and opportunities for therapy (article here)

- Journal Article: Neurotransmitter modulation by the gut microbiota (article here)

- Journal Article: Human nutrition, the gut microbiome and the immune system (article here)

- Journal Article: The microbiome: A key regulator of stress and neuroinflammation (article here)

- Journal Article: Current Understanding of Gut Microbiota in Mood Disorders: An Update of Human Studies (article here)

- Journal Article: Role of gut microbiota in brain function and stress-related pathology (article here)

- Journal Article: Intestinal permeability – a new target for disease prevention and therapy (article here)

- AUSMED E-Learning: Gut Microbiota Health and Wellbeing (link here)

- Journal Article: A review of lifestyle factors that contribute to important pathways associated with major depression: Diet, sleep and exercise (article here)

- Journal Article: ‘Gut health’: a new objective in medicine? (article here)

- Journal Article: Impact of the gut microbiota on inflammation, obesity, and metabolic disease (article here)

- Journal Article: The Gut Microbiome as a Major Regulator of the Gut-Skin Axis (link here)

- Journal Article: Dietary Modulation of the Human Colonic Microbiota: Introducing the Concept of Prebiotics (link here)

- Journal Article: Prebiotics: why definitions matter (link here)

- Journal Article: Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics (link here)

- Article: ISAPP: Prebiotics (link here)

- Journal Article: Clinical uses of probiotics (link here)

- Journal Article: Six-week Consumption of a Wild Blueberry Powder Drink Increases Bifidobacteria in the Human Gut (link here)

- Journal Article: Effects of Almond and Pistachio Consumption on Gut Microbiota Composition in a Randomised Cross-Over Human Feeding Study (link here)

- Journal Article: Impact of Increasing Fruit and Vegetables and Flavonoid Intake on the Human Gut Microbiota (link here)

- Journal Article: Effect of Apple Intake on Fecal Microbiota and Metabolites in Humans (link here)

- Journal Article: Prebiotic Effect of Fruit and Vegetable Shots Containing Jerusalem Artichoke Inulin: A Human Intervention Study (link here)

- Journal Article: Dietary effects on human gut microbiome diversity (link here)

- Journal Article: The Role of Gut Microbiota in Intestinal Inflammation with Respect to Diet and Extrinsic Stressors (article here)

- Journal Article: Gut microbiota functions: metabolism of nutrients and other food components (article here)

- Journal Article: Stress and the gut microbiota-brain axis (article here)

- Journal Article: Neurotransmitter modulation by the gut microbiota (article here)

- Journal Article: Current Understanding of Gut Microbiota in Mood Disorders: An Update of Human Studies (article here)

- AUSMED E-Learning: Gut Microbiota Health and Wellbeing (link here)

- Journal Article: A review of lifestyle factors that contribute to important pathways associated with major depression: Diet, sleep and exercise (article here)

- Journal Article: ‘Gut health’: a new objective in medicine? (article here)

- Journal Article: Impact of the gut microbiota on inflammation, obesity, and metabolic disease (article here)

- Journal Article: The association of sleep and pain: An update and a path forward (article here)

- Journal Article: The Important Role of Sleep in Metabolism (article here)

- Journal Article: Role of Sleep and Sleep Loss in Hormonal Release and Metabolism (article here)